Genitive: Crucis

Abbreviation: Cru

Size ranking: 88th

Origin: Petrus Plancius

The smallest of all the 88 constellations. Its stars were known to the ancient Greeks, and were catalogued by Ptolemy in the Almagest, but at that time were regarded as part of the hind legs of Centaurus, the centaur, rather than as a separate constellation. They subsequently became lost from view to Europeans because of the effect of precession, which causes a gradual drift in the position of the celestial pole against the stars, and were rediscovered during the 15th and 16th centuries by seafarers venturing south.

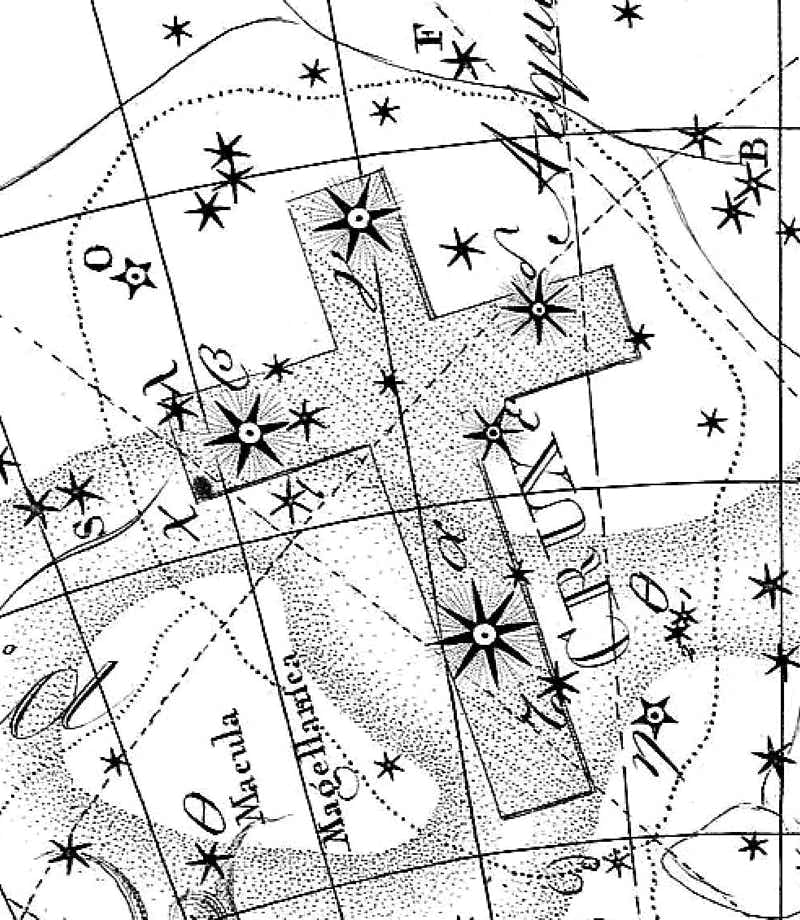

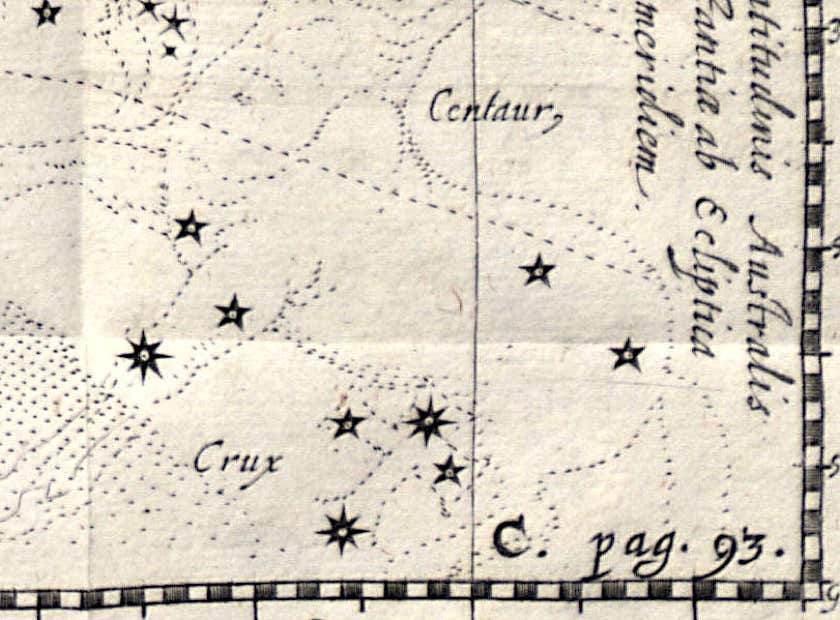

Crux lies under the hind legs of Centaurus, and its stars were regarded by the Greeks as part of Centaurus. It contains a dark cloud of dust known to modern astronomers as the Coalsack, but named Macula Magellanica on this illustration from Chart XX of the Uranographia star atlas of Johann Bode (1801). The dark patch below left of Beta Crucis is the Kappa Crucis cluster, popularly known as the Jewel Box.

As early as 1455 the Venetian explorer Alvise Cadamosto (c.1432–83), observing from off the west coast of Africa around latitude 13° north, wrote of seeing ‘six stars low above the sea, clear and bright and large … which we took to be the chariot of the south’. Evidently those six stars were Alpha and Beta Centauri and the four main members of the Cross. His mention of the ‘chariot of the south’ (i.e. a southern version of the Plough) was a reference to the widespread belief at that time that the stars around the south pole would mirror those of the north.

Early drawings of the Southern Cross

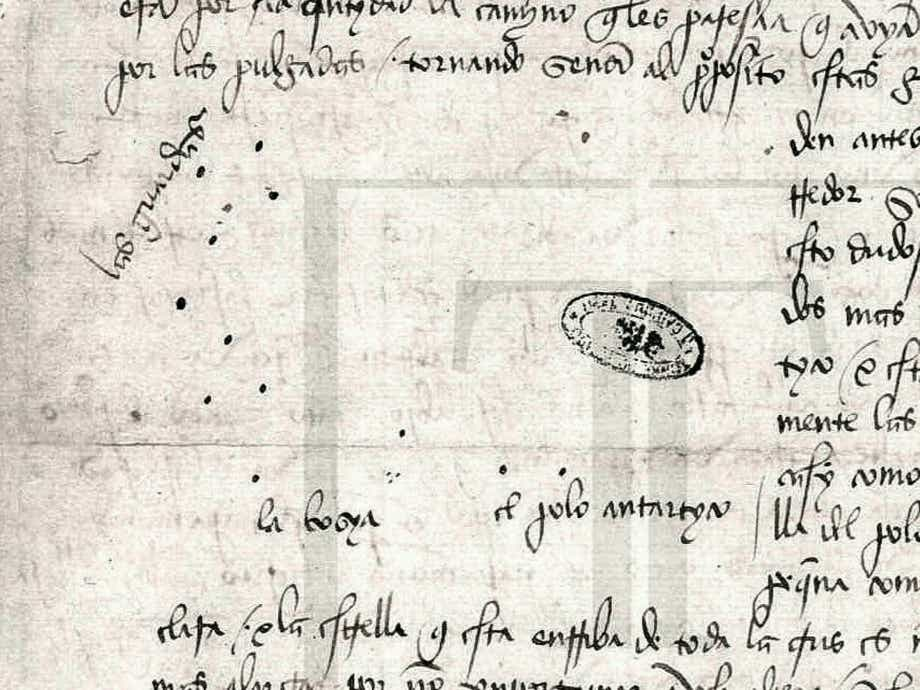

The first known sketch of the area around the south celestial pole was made in 1500 by João Faras, also known as Mestre João (i.e. Master John), an astronomer-cum-navigator with a fleet led by the Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral. From the coast of South America around latitude 16° south, in the area that is now Brazil, Faras wrote a letter to King Manuel of Portugal describing the southern sky, including what are clearly the five stars of the modern Crux. He termed these stars The Guards, i.e. of the south pole, and also referred to them as the Cross, an indication that this name was already coming into general use.

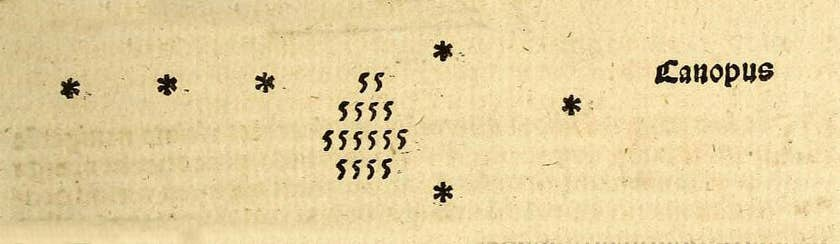

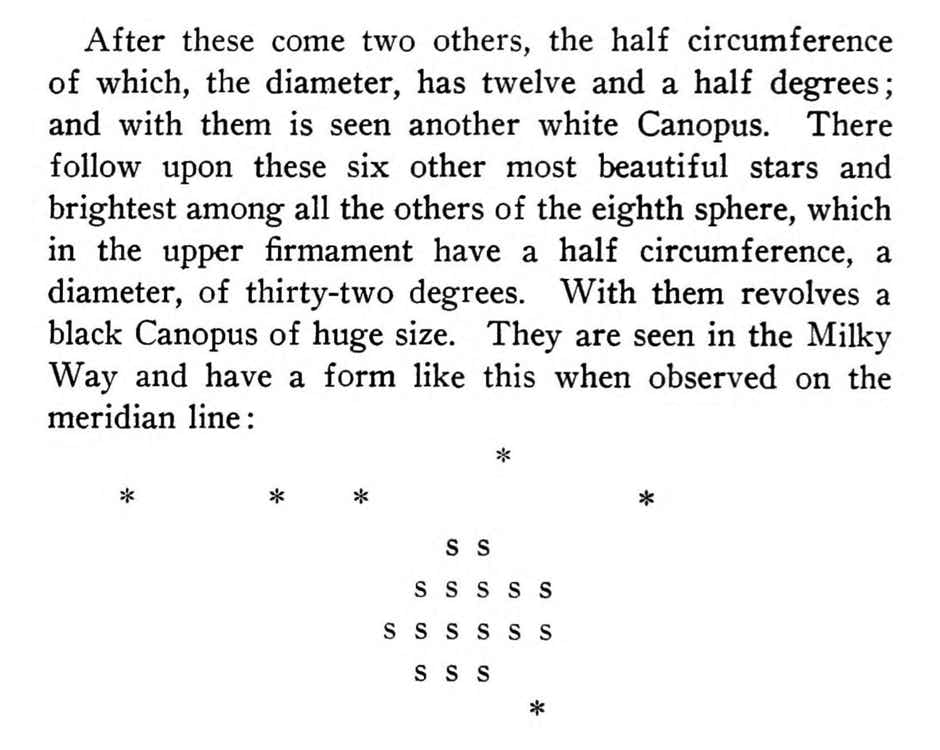

During a voyage to South America in 1501–02 the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512) reported seeing ‘six stars, the most beautiful and bright among all others in the heavenly sphere… With them is a black canopus of immense size.’ Vespucci’s original drawing of this area has been lost but there is a crude printer’s copy from which it seems clear that the six ‘beautiful and bright’ stars were Alpha and Beta Centauri plus the four brightest stars of the Southern Cross, while the ‘black canopus‘ can only refer to the dark Coalsack Nebula.

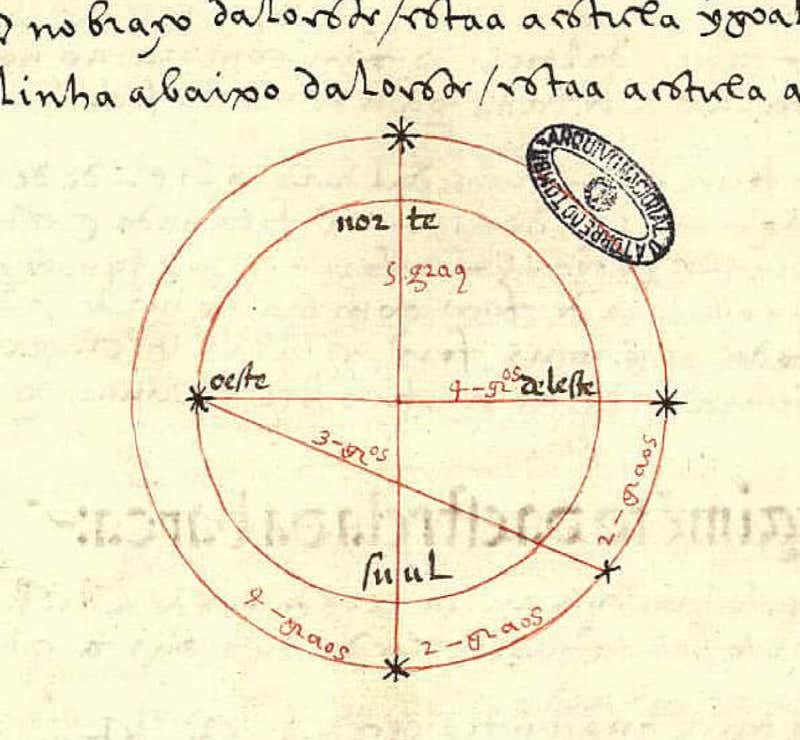

Another Portuguese explorer, João de Lisboa (c.1470–1525), made several voyages into the southern hemisphere in the early 16th century from which he compiled a book on the use of the compass at sea, Tratado da agulha de Marear (1514). In this he wrote: ‘You will know that in the Southern Cross there are five stars, four of which are large, of the second magnitude, and one of the fifth magnitude.’ He went on to give a diagram of the Cross with measurements of the declinations of the five stars as a guide to finding latitude. João’s explicit use of the term ‘Cruzeiro do Sul’ (i.e. Southern Cross) shows that this name was by then firmly established, at least among navigators if not yet astronomers.

Corsali’s sketch

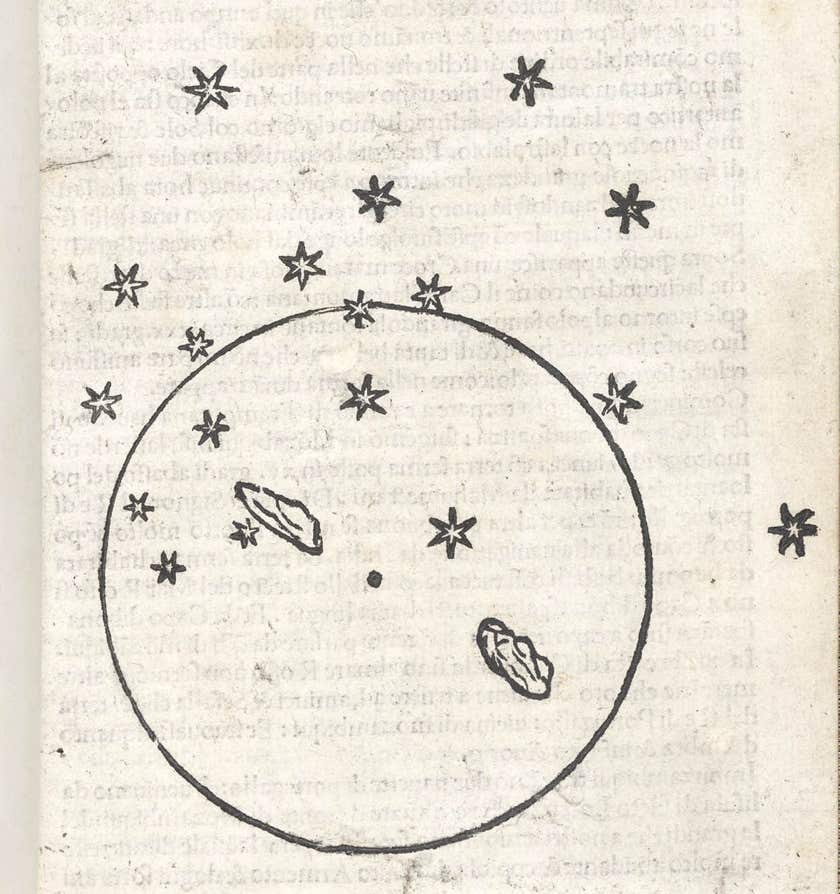

Probably the best-known early depiction of the Cross and its surroundings was a sketch made in 1516 by the Italian explorer Andrea Corsali (1487–15??) during a voyage on a Portuguese ship around the Cape of Good Hope to India. Corsali included this sketch in a letter to his patron, Giuliano de Medici (1479–1516), the wealthy ruler of Florence, and it was subsequently copied as a woodcut in a printed booklet (see illustration below).[note] Corsali famously described the pattern as ‘a marvellous cross … of such beauty that to me no celestial sign seems comparable’ (‘di tanta belleza che non mi pare anissuno celeste segno conparando’). By then navigators were regularly using the cross as a pointer to the south celestial pole and it was adopted by astronomers as a separate constellation by the end of the 16th century.

Diagram of the stars around the south celestial pole by the Italian explorer Andrea Corsali (1487–15??), privately published in 1516. The two Magellanic Clouds are clearly seen either side of the pole, with the five stars of Crux standing vertically at the centre and Alpha and Beta Centauri (the ‘pointers’) at the right. Corsali’s diagram shows the sky as it would appear on a celestial globe, i.e. a mirror image of the view from Earth, as pointed out by the Dutch historian Elly Dekker. (State Library of New South Wales)

The Southern Cross on globes and charts

Crux first appears in its modern form on the celestial globes by the Dutch cartographers Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius in 1598 and 1600; Plancius had earlier shown a stylized southern cross in a completely different part of the sky, south of Eridanus, based on Corsali’s sketch. Perhaps the first person to recognize the true identity of the stars of the southern cross was the English geographer and explorer Robert Hues (1553–1632), who was clearly familiar with Ptolemy’s catalogue. Hues had seen the stars of the southern cross for himself during two southern voyages in 1586–8 and 1591–2 and realized that ‘they are no other than the brighter stars which are in the Centaur’s feet’, as he pointed out in his book of 1594 called Tractatus de globis et eorum usu (Treatise on Globes and Their Use).[note]

Hues’s book was translated into Dutch by Plancius’s colleague Jodocus Hondius in 1597. In that same year, Plancius received the first accurate observations of the southern stars made by his countryman Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser. There could then have been no doubt that Hues’s identification of the stars as part of Centaurus was correct.

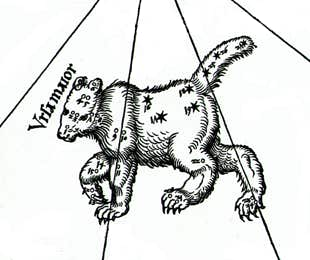

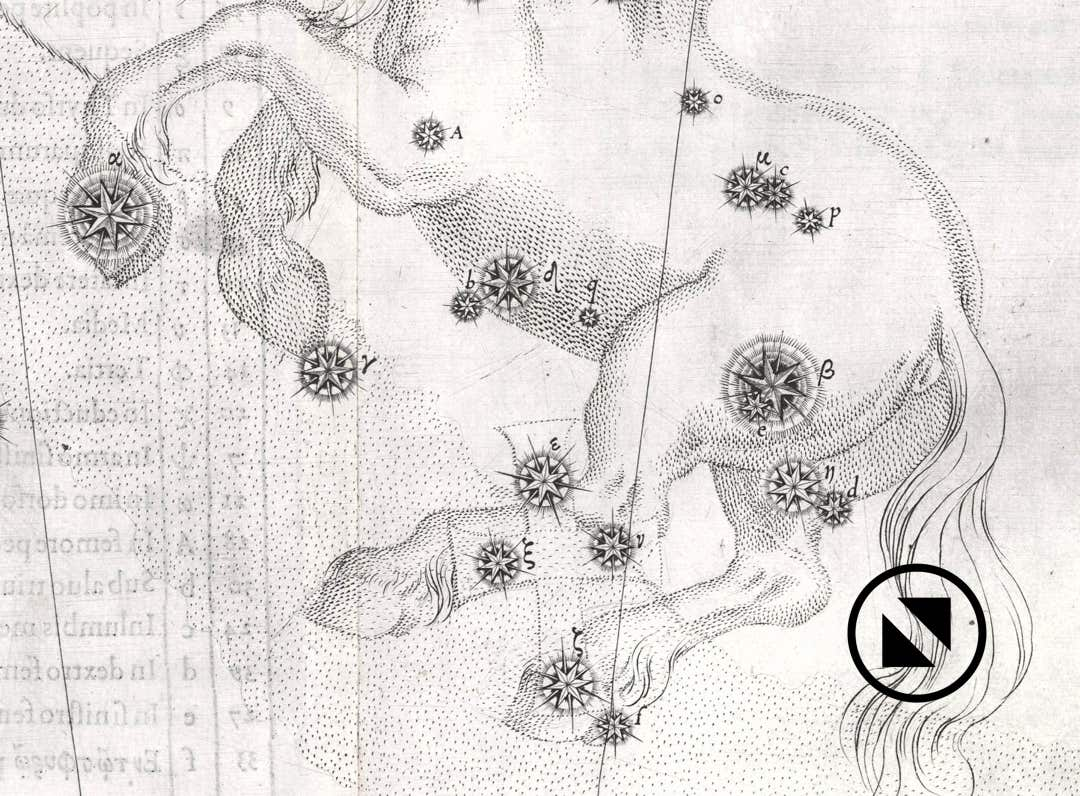

Benefiting from this revelation, Johann Bayer drew the cross over the hind legs of the centaur on his Uranometria atlas of 1603, although he still labelled its stars as part of Centaurus (see illustration below). In his accompanying catalogue Bayer described these four stars as ‘Modernis Crux, Ptolemaeo pedes Centauri’ (i.e. the modern Crux, Ptolemy’s feet of the Centaur).

Crux as shown by Johann Bayer on his Uranometria atlas of 1603, overlying the rear legs of the centaur. Bayer labelled the four stars of the cross Epsilon, Xi, Nu, and Zeta Centauri; these are the present-day Gamma, Beta, Delta, and Alpha Crucis. The modern letters were allocated by the Frenchman Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in his southern star catalogue of 1756. Star positions and magnitudes in this region, based on the listing in Ptolemy’s Almagest, contain large errors. Note that the present-day Beta Centauri, on the centaur’s right forefoot, was labelled Gamma by Bayer and is too faint, while Bayer’s Beta Centauri was positioned on the centaur’s hindquarters where no such bright star exists.

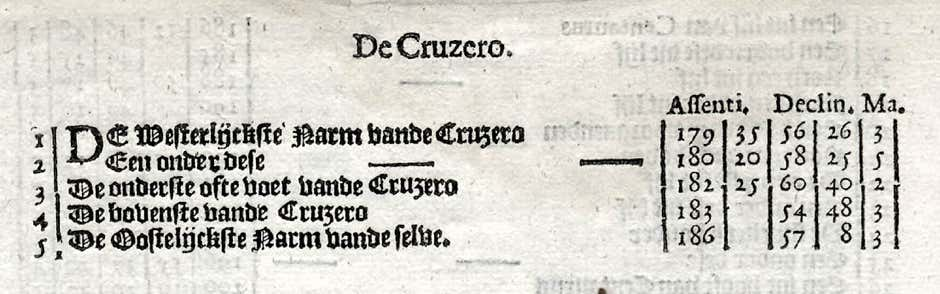

Crux was listed as a separate constellation for the first time under the name De Cruzero in the southern star catalogue of another Dutch seafarer, Frederick de Houtman, published in 1603; he had evidently seen globes made a few years earlier by Hondius and Blaeu on which Crux was shown separately from Centaurus. The first printed star chart (as distinct from a globe) to show Crux separately from Centaurus was that of the German astronomer Jacob Bartsch in 1624.

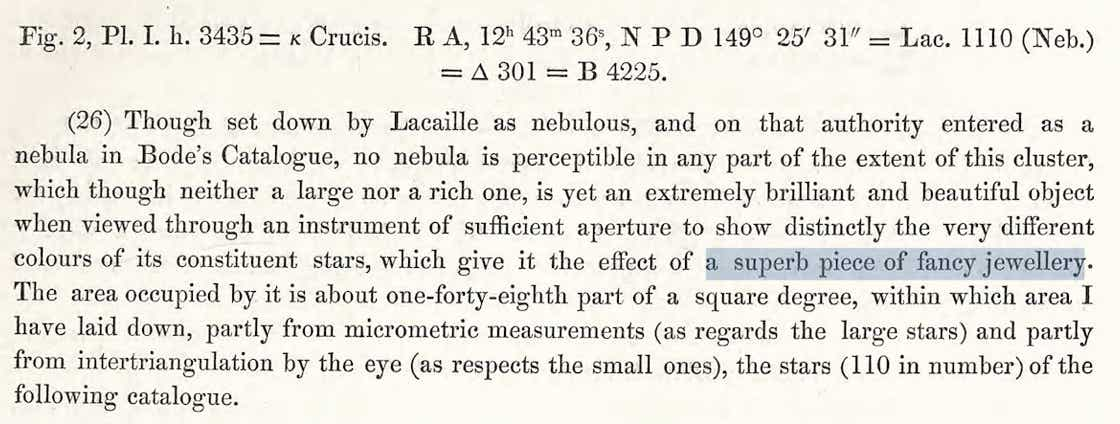

The stars of Crux, a Coalsack, and a False Cross

The constellation’s brightest star, magnitude 0.8, is called Acrux, a name originally applied by modern navigators from its scientific designation Alpha Crucis. At declination –63°.1, Acrux is the most southerly first-magnitude star. The names Becrux and Gacrux for Beta and Gamma Crucis have a similar modern origin, although Becrux is now only an unofficial alternative to its IAU-recognized name of Mimosa. Near Beta Crucis lies the Kappa Crucis star cluster (NGC 4755) popularly known as the Jewel Box because John Herschel described it as resembling ‘a superb piece of fancy jewellery’.

Crux contains a famous dark cloud of gas and dust called the Coalsack Nebula, which appears in silhouette against the bright Milky Way background. This was first described by Amerigo Vespucci in 1502, in the same account as his description of the Cross (see above), who referred to it as a ‘black canopus of immense size, seen in the Milky Way’.

There is a second cross nearby in the southern sky, larger and fainter than the real thing. Known as the False Cross, it consists of stars from two adjoining constellations: Epsilon and Iota Carinae plus Delta and Kappa Velorum, all of second magnitude.

Chinese associations

Chinese astronomers worked at a similar latitude to Ptolemy, so they were able to see the same stars as he did, including those of Crux. However, the effect of precession gradually carried this part of the southern sky below their horizon about 1,500 years ago, as it did for European astronomers.

The stars we know as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta Crucis were once part of the constellation Kulou, which represented a military depot. In their book The Chinese Sky During the Han, Sun and Kistemaker show these four stars forming a diamond-shaped tower at the southern end of the depot. Later, though, this feature was placed farther north among the stars of Centaurus. Probably Chinese astronomers gradually moved this part of Kulou northwards on their charts as Crux became lost from view. A similar transfer to more northerly stars over time affected other Chinese constellations in this region of sky, for the same reason.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

STARS OF CRUX LISTED IN THE ALMAGEST

Ptolemy’s number in Centaurus and description

31 The star on the knee-bend of the right [hind] leg

32 The star in the hock of the same leg

33 The star under the knee-bend of the left [hind] leg

34 The star on the frog of the hoof on the same leg

Modern name

Gamma Crucis

Beta Crucis

Delta Crucis

Alpha Crucis

Identifications and descriptions in English are from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998). The identifications are highly uncertain due to large positional errors.

This simple sketch made in 1500 from South America by João Faras is the first known drawing by a European of the area around the south celestial pole. At top left are the five stars of the Southern Cross, which Faras labelled Las Guardas (i.e. The Guards), while at lower centre is the area of the south celestial pole (‘el polo antartyco’). The map is clearly distorted, since the axis of the Cross does not point towards the pole. (Torre do Tombo National Archive)

Amerigo Vespucci sketched a view of Alpha and Beta Centauri and the four main stars of the southern cross, with the ‘black canopus’ of the Coalsack between them, in 1502 after a voyage to South America. The original diagram has been lost, but this is a printer’s attempt at a typeset representation of it.

Diagram of the Southern Cross by the Portuguese navigator João de Lisboa (i.e. John of Lisbon) from his Tratado da agulha de Marear of 1514 showing how to use the stars of the Cross for determining latitude. The five main stars are drawn in black, and their distances from the south celestial pole in degrees are given in the accompanying text. João recommended sighting on the star at the foot of the Cross (the modern Alpha Crucis) which he measured to be 30° from the pole. North is at the top. (Torre do Tombo National Archive)

This diagram became more widely known in 1550 when reproduced in the Primo volume delle navigationi et viaggi by the Venetian geographer Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485–1557).

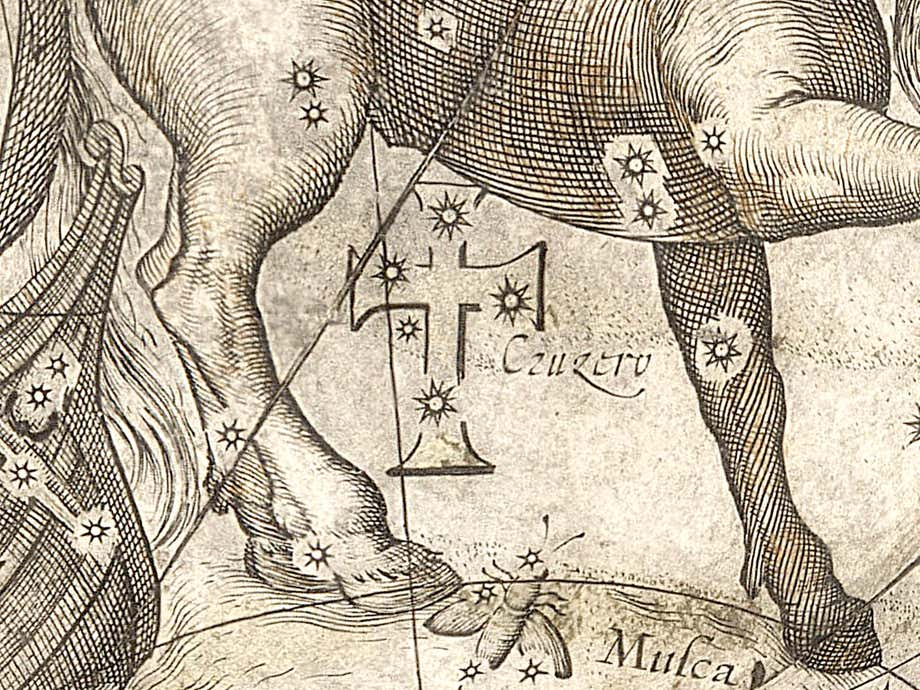

The Southern Cross, here named Cruzero, seen under the body of Centaurus on the celestial globe of 1600 by Jodocus Hondius. Beneath it is Musca, the fly, which went unnamed on this globe. Click on the image for a link to a 3D version of the globe at the BnF.

An imaginary Southern Cross placed at the end of Eridanus, seen on a small chart of the southern sky in the margin of Petrus Plancius’s world map of 1592. The figure at left is a short-lived Plancius invention called Polophylax. Plancius has given Crux the alternative name Stauros from the Greek Σταυρός meaning ‘cross’ (the word is partially obscured due to bad printing). Only one surviving copy of this 1592 map is known, in the Colegio del Corpus Christi, Valencia.

In 1590 the English mathematician Thomas Hood (1556–1620) had written in his book The Use of the Celestial Globe in Plano that the stars of the Southern Cross ‘are none other then [sic] those which are in the hinder feete of the Centaure’. It seems highly likely that Hood’s source was Hues, after his first voyage.

Frederick de Houtman listed the five main stars of Crux separately from Centaurus in his southern star catalogue of 1603.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu’s celestial globe of 1602 showed Crux separately from Centaurus under the name Cruzero. The constellation figures on Blaeu’s globe were drawn by the Dutch artist Jan Pieterszoon Saenredam (1565–1607) and de Houtman seems to have used them as a model when describing the positions of the southern stars in his catalogue published in 1603, particularly in the case of of Argo.

The Southern Cross, here named Cruzero, seen under the body of Centaurus on the celestial globe of 1600 by Jodocus Hondius. Beneath it is Musca, the fly, which went unnamed on this globe. Click on the image for a link to a 3D version of the globe at the BnF.

Crux was shown as a separate constellation on a chart in Jacob Bartsch’s Usus Astronomicus Planisphaerii Stellati (‘Astronomical Use of the Stellar Planisphere’), published in 1624.

John Herschel’s description of the Kappa Crucis cluster from his book Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope, published in 1847. He listed 110 stars in the cluster from 7th to 16th magnitude.

Amerigo Vespucci’s description of the Coalsack nebula (‘a black Canopus of huge size’) after his voyage to South America in 1501–02 in a letter to Lorenzo Pietro Francesco di Medici. The ‘white Canopus’ also mentioned is one of the Magellanic Clouds. The diagram is a crude attempt to represent Alpha and Beta Centauri and the four main stars of the southern cross, with the ‘dark canopus’ of the Coalsack between them. Some of Vespucci’s other claims made in his report, such as noting ‘as many as 20 stars as bright as we see Venus and Jupiter’, are quite clearly exaggerated.

The Southern Cross, left of centre, and the False Cross at right, seen against the hull of Argo, on Edmond Halley’s southern star chart of 1678. Halley’s short-lived invention of Robur Carolinum lies between them. The modern designations of the stars in the False Cross are Kappa and Delta Velorum (top and right of the cross), and Iota and Epsilon Carinae (left and bottom), all of second magnitude.