Additional images of Argo

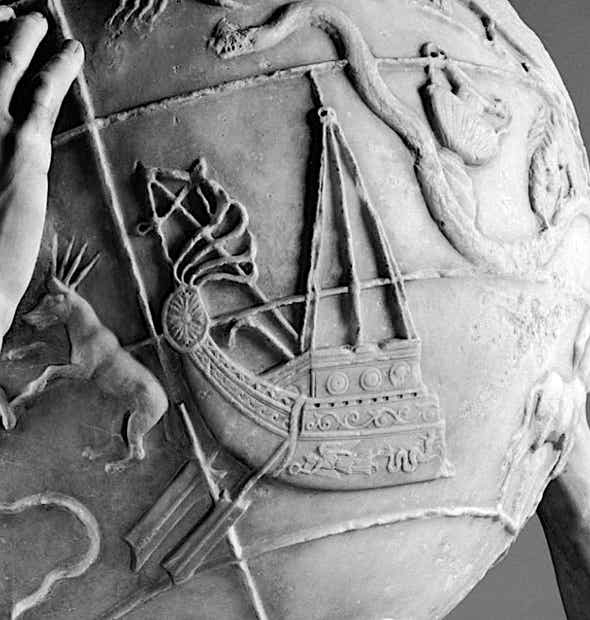

▲ Argo seen in bas-relief on the Farnese Atlas, an ancient Roman celestial globe dating from the second century AD but thought to be a copy of a Greek original some 300 years older. As such it is our earliest view of the ancient Greek constellations described by Aratus and Eratosthenes. At right Argo is seen on a drawing of the globe by Louis-Philippe Boitard (fl. 1733–67) published in 1747. The Farnese globe’s Argo has a mast supported by four guy ropes, an ornamented stern protected by a shield, a row of smaller shields along the side, and two steering paddles at the stern, but no oars for rowing. This might seem a strange omission for a supposed 50-oared galley, but Eratosthenes had made no mention of any such oars; he simply said that the ship had been placed in the sky up to the mast, along with the steering oars, and the sculptor of the Farnese globe evidently followed that description. (Ptolemy in the Almagest did not mention any rowing oars either.) No stars are shown on the Farnese globe, only the figures of the constellations along with various coordinate lines. Next to Argo is Canis Major with four rays emanating from its head, presumably to symbolize the brilliance of Sirius. (Images: Luigi Spina, left; author’s collection, right)

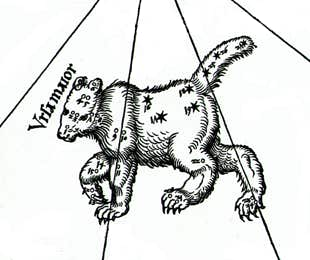

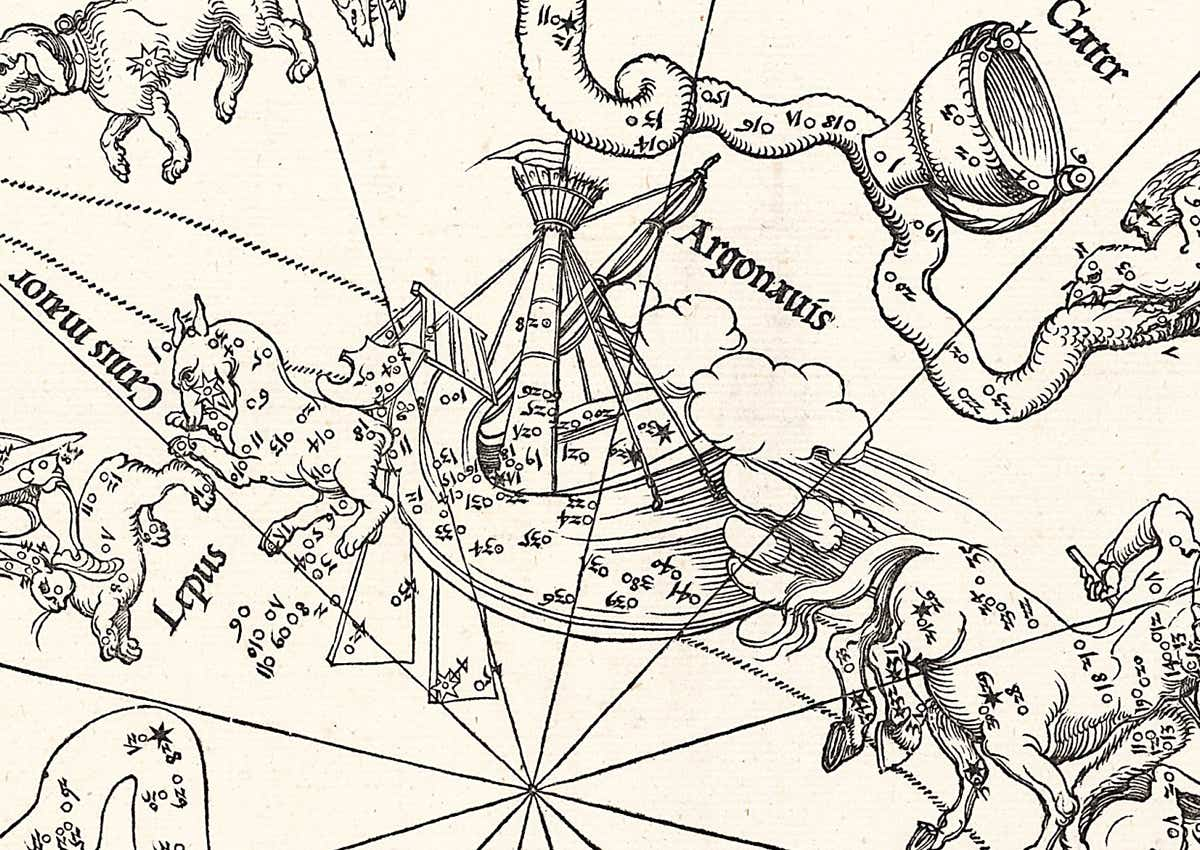

Dürer 1515

▲ One of the first astronomically accurate depictions of Argo was on the celestial hemispheres of Albrecht Dürer published in 1515. Star positions were taken from Ptolemy’s catalogue in the Almagest, updated to the year 1500 by the German astronomer Conrad Heinfogel. Although broadly similar to the depiction of Argo on the Farnese globe, there are several differences. Dürer supplied the ship with a sturdier mainmast than on the Farnese globe, topped by a crow’s nest. Dürer’s Argo has a spar with reefed sail and a covered aftercastle, but no row of shields along the hull. Ptolemy had mentioned shields in the Almagest, so their omission is a surprise. On the other hand Ptolemy had not mentioned a sail, but after Dürer it became conventional to equip Argo with one. No rowing oars are shown, only two steering paddles, as on the Farnese globe. To account for the lack of a bow, Dürer drew the forward part of the ship as vanishing into a bank of clouds between it and the hind legs of Centaurus. The stars on Dürer’s chart are numbered in the order they were listed by Ptolemy (the illustration above is oriented so that the ship is the right way up, but the numbers appear upside-down). Star 44, at the end of the more southerly steering oar, is the brilliant Canopus. Dürer drew his constellations as though they were on a celestial globe, so the ship is reversed from the way it appears in the sky.

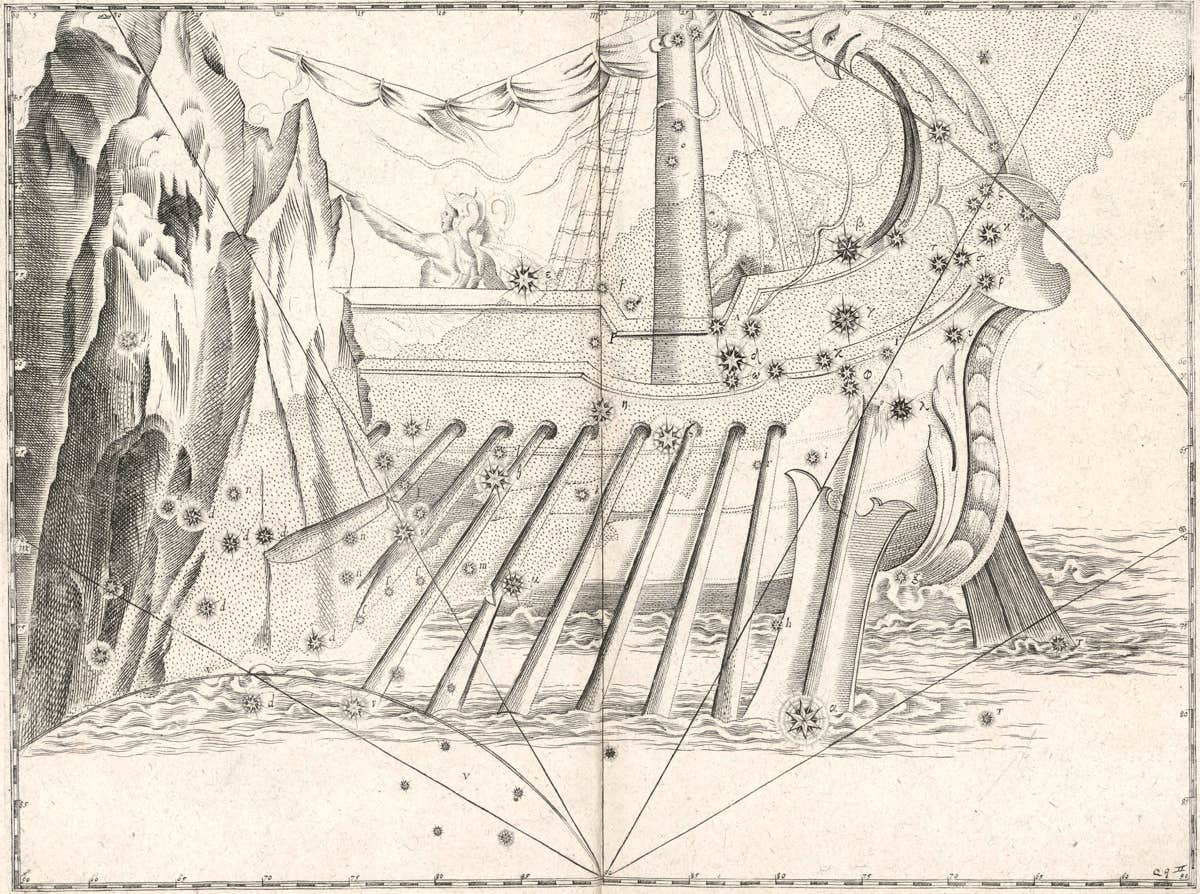

Bayer 1603

▲ Whatever Johann Bayer’s Uranometria atlas of 1603 may have lacked in strict positional accuracy it more than made up for in artistic merit, as in this illustration of the Argo passing between the Clashing Rocks at the mouth of the Black Sea. Bayer depicts some of the ship’s oars splintering on the rocks, and the yard arm with the furled sail also appears to have snapped. Canopus lies on the blade of the port-side steering oar, as described by Ptolemy. Bayer’s labelling of the stars with Greek and Roman letters was comprehensively revised by Lacaille a century and a half later.

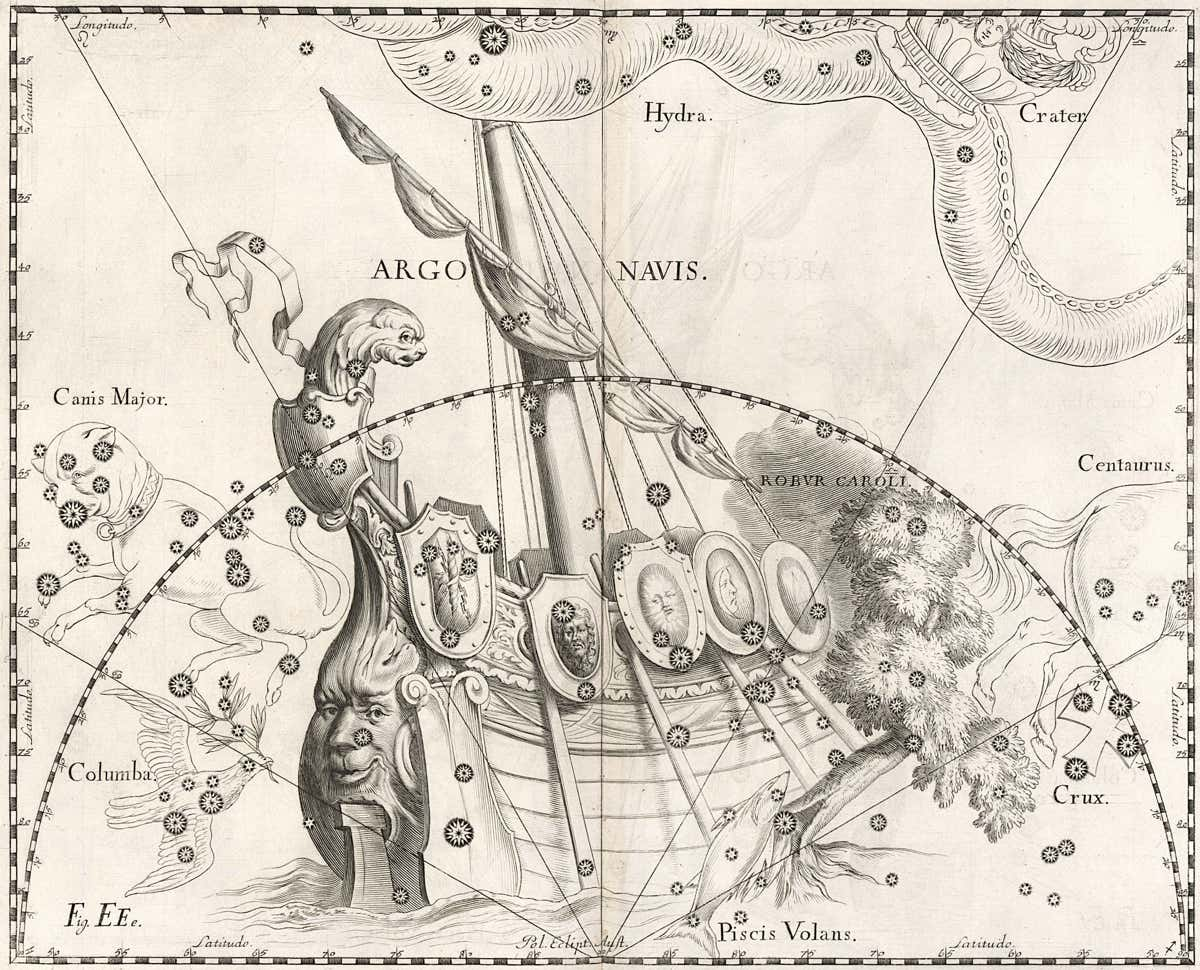

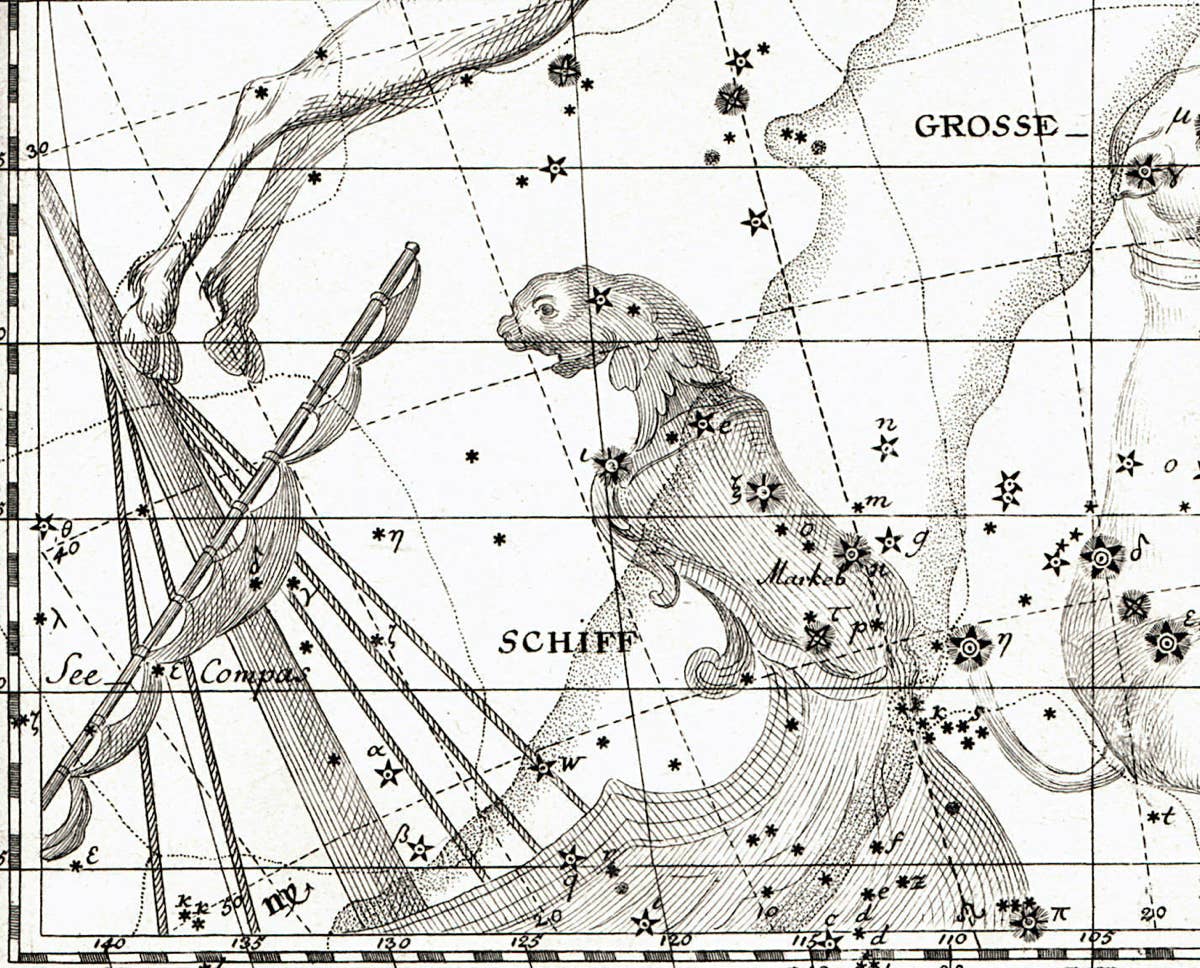

Hevelius 1690

▲ Johannes Hevelius depicted an even more elaborate Argo in his Firmamentum Sobiescianum of 1690 (he seems to have got his inspiration from this globe by Willem Janszoon Blaeu). As with all the constellations on his charts, Hevelius showed Argo as a mirror image, as it would appear on the surface of a globe. Here, the spar around which the sail is furled is slanted at an angle to the main mast. Such an arrangement is termed a lateen rig and was common in the Mediterranean. Again, Canopus is prominent on the large steering paddle at the stern. The Clashing Rocks seen in Bayer’s representation have been replaced by Edmond Halley’s recent invention Robur Carolinum, here named Robur Caroli.

Bode 1782

▲ In Johann Bode’s 1782 star atlas Vorstellung der Gestirne, a smaller forerunner of the giant Uranographia, Argo made only a partial appearance on one chart. Bode showed it with its sail furled to a lateen-type yard arm, as had John Flamsteed in his Atlas Coelestis of 1729. Compare this with Bode’s later depiction of Argo in Uranographia, shown on the previous page, where there is no main mast and the yard arm appears to emerge from the sternpost like a spar. (Image: Author’s collection.)

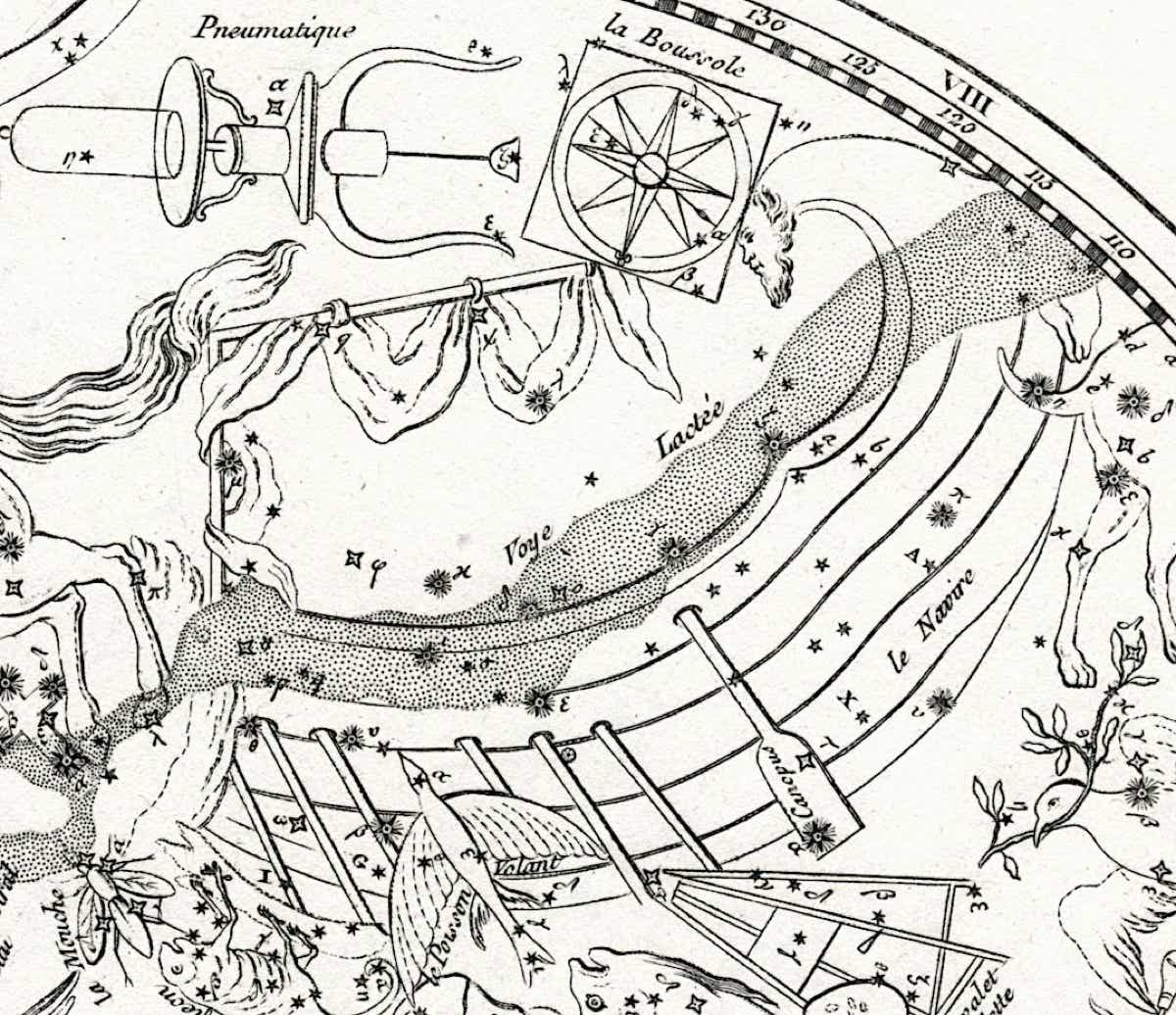

Lacaille 1756

▲ Nicolas Louis de Lacaille’s version of Argo on his planisphere of the southern skies published in 1756, as seen in a copy from Jean Fortin’s Atlas Céleste. Lacaille showed the ship’s mast as either bent or broken; alternatively, perhaps the vertical part is intended to be the main mast and the horizontal part the yard arm. Lacaille referred to it as ‘the horizontal mast, or the spar on which the sail is reefed’. Above the sails Lacaille introduced a new constellation, la Boussole, representing a marine compass; this is now known as Pyxis. In the catalogue accompanying this chart Lacaille split Argo into three parts: Carina (Corps), Puppis (Pouppe), and Vela (Voilure), although there is no indication of this on his chart. In the second edition of the planisphere, published in 1763, the French names were replaced by Latin ones. For a zoomable version of the 1763 chart, see here. (Image: Author’s collection.)

Blaeu/Saenredam 1602

▲ At the start of the 17th century the Dutch artist Jan Pieterszoon Saenredam (1565–1607) reimagined Argo as a three-masted galleon in full sail, as seen on the globe above made in 1602 by the Dutch cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571–1638). Saenredam’s Argo is not at all what Ptolemy or the mythologists had in mind. Among the numerous non-classical features, Canopus is positioned on a single stern rudder, while above it a sailor dangles a lead weight on a line to plumb the depth of the surrounding waters. (Incidentally, the star on the plumb weight later became Lacaille’s Beta Pictoris.) The southern stars on this globe are from the observations made by Keyser on the Eerste Schipvaart, even though Blaeu claimed they were from a later survey by Fredrick de Houtman. In fact de Houtman must have seen this globe before completing his catalogue, which was published in 1603, as he clearly had Saenredam’s galleon in mind when describing the positions of the stars in Argo. Edmond Halley (below) enthusiastically adopted the modernized Argo, adding his own British twist, but most chart makers stuck to the classical depiction of the ship. (British Library)

Halley 1678

▲ Flying a red ensign from the stern and the Cross of St George from its topmast, Argo appears to have become an English merchant ship in its depiction on Edmond Halley’s southern star chart of 1678. These flags were doubtless a tribute to the East India Company whose ships had transported Halley to and from St Helena from where he observed the southern sky in 1677–8. Halley’s newly invented constellation Robur Carolinum lies across the ship’s bow with billowing clouds above it; the clouds were one classical feature that he did retain. (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Argo seen on a globe by Willem Janszoon Blaeu, first issued in 1616 and with several later editions. In this depiction Argo has six large rowing oars and two large steering paddles; Canopus is on the end of the nearside one. Several small shields lie along the top of the ship’s hull, as described by Ptolemy and shown on the Farnese globe but ignored by many chart makers. This is a far more classical view of Argo than on Blaeu’s earlier globes (see below). Hevelius was clearly influenced by Blaeu’s globe when he drew his own version of Argo, although he reduced the number of oars to four and made changes to the ship’s stern. For a less brightly coloured version of the globe see here.