Genitive: Lyrae

Abbreviation: Lyr

Size ranking: 52nd

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Λύρα

A compact but prominent constellation, marked by the fifth-brightest star in the sky, Vega. Mythologically, Lyra (Λύρα in Greek) was the lyre of the great musician Orpheus, whose venture into the Underworld is one of the most famous of Greek stories. It was the first lyre ever made, having been invented by Hermes, the son of Zeus and Maia (one of the Pleiades). Hermes fashioned the lyre from the shell of a tortoise that he found browsing outside his cave on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia. Hermes cleaned out the shell, pierced its rim and tied across it seven strings of cow gut, the same as the number of the Pleiades. He also invented the plectrum with which to play the instrument.

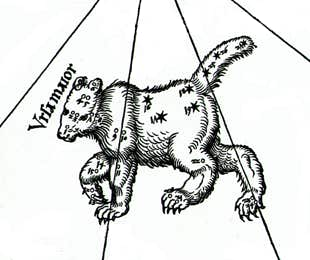

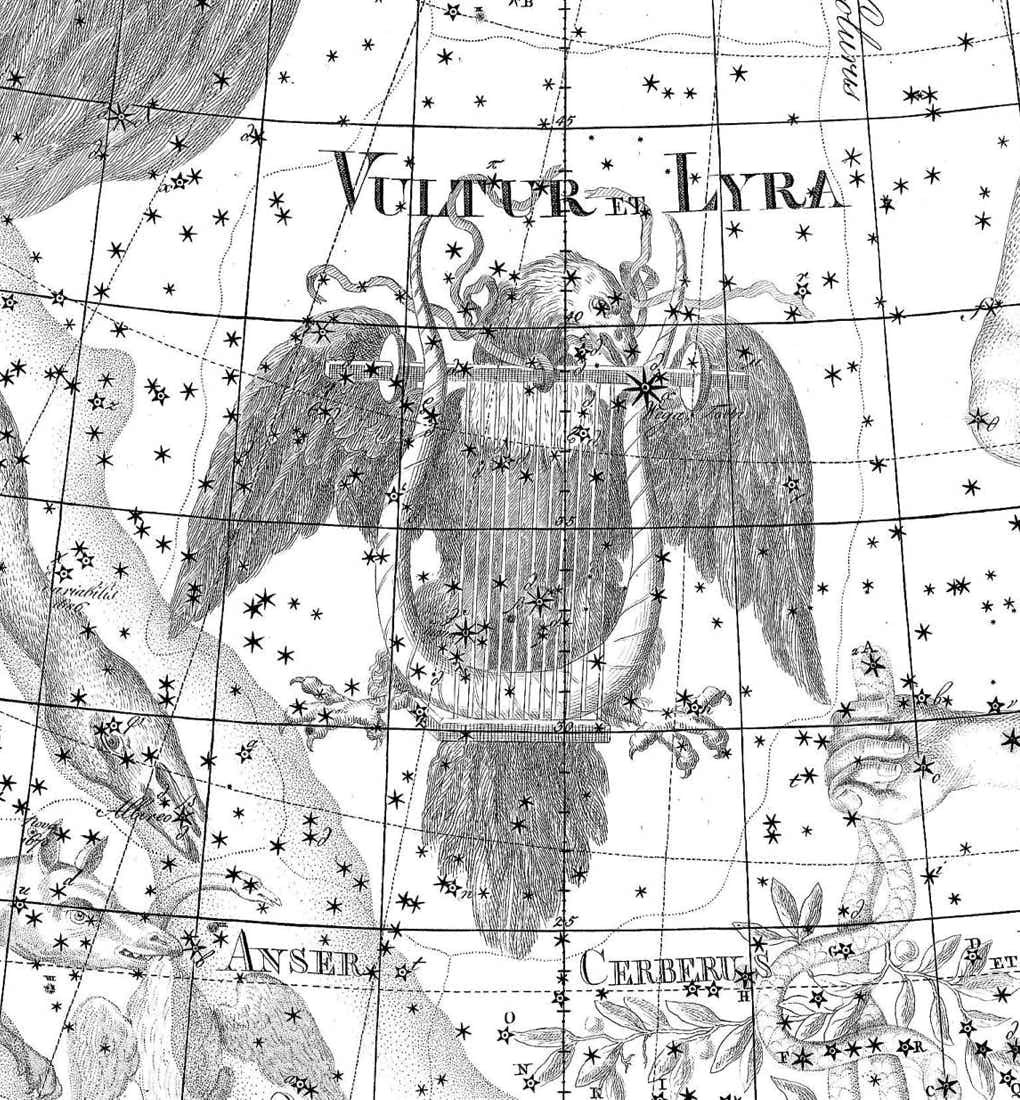

Lyra was frequently visualized as an eagle or vulture as well as a lyre; both are shown on this engraving from Chart VIII of Johann Bode’s Uranographia (1801). Near the tip of the bird’s beak is the bright star Vega, here spelled Wega; Bode also gave this star the alternative name Testa (Latin for shell) in reference to the tortoise shell from which the lyre was supposedly made by Hermes.

Both Bayer and Bode showed the lyre tied around the eagle’s neck with ribbons, whereas Hevelius drew the eagle grasping the lyre in its claws. Flamsteed’s atlas did not show the eagle at all, just the lyre.

The lyre got Hermes out of trouble after a youthful exploit in which he stole some of Apollo’s cattle. Apollo angrily came to demand their return, but when he heard the beautiful music of the lyre he let Hermes keep the cattle and took the lyre in exchange. Eratosthenes says that Apollo later gave the lyre to Orpheus to accompany his songs.

Orpheus was the greatest musician of his age, able to charm rocks and streams with the magic of his songs. He was even reputed to have attracted rows of oak trees down to the coast of Thrace with the music of his lyre. Orpheus joined the expedition of Jason and the Argonauts in search of the golden fleece. When the Argonauts heard the tempting song of the Sirens, sea nymphs who had lured generations of sailors to destruction, Orpheus sang a counter melody that drowned the Sirens’ voices.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Later, Orpheus married the nymph Eurydice. One day, Eurydice was spied by Aristaeus, a son of Apollo, who attacked her in a fit of passion. Fleeing from him, she stepped on a snake and died from its poisonous bite. Orpheus was heartbroken; unable to live without his young wife, Orpheus descended into the Underworld to plead for her release. Such a request was unprecedented. But the sound of his music charmed even the cold heart of Hades, god of the Underworld, who finally agreed to let Eurydice accompany Orpheus back to the land of the living on one solemn condition: Orpheus must not at any stage look behind him until the couple were safely back in daylight.

Orpheus readily accepted, and led Eurydice through the dark passage that led to the upper world, strumming his lyre to guide her. It was an unnerving feeling to be followed by a ghost. He could never be quite sure that his beloved was following, but he dared not look back. Eventually, as they approached the surface, his nerve gave out. He turned around to confirm that Eurydice was still there – and at that moment she slipped back into the depths of the Underworld, out of his grasp for ever.

Orpheus was inconsolable. He wandered the countryside, plaintively playing his lyre. Many women offered themselves to the great musician in marriage, but he preferred the company of young boys.

The death of Orpheus

There are two accounts of the death of Orpheus. One version, told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, says that the local women, offended at being rejected by Orpheus, ganged up on him as he sat singing one day. They began to throw rocks and spears at him. At first his music charmed the weapons so that they fell harmlessly at his feet, but the women raised such a din that they eventually drowned the magic music and the missiles found their mark.

Eratosthenes, on the other hand, says that Orpheus incurred the wrath of the god Dionysus by not making sacrifices to him. Orpheus regarded Apollo, the Sun god, as the supreme deity and would often sit on the summit of Mount Pangaeum awaiting dawn so that he could be the first to salute the Sun with his melodies. In retribution for this snub, Dionysus sent his manic followers to tear Orpheus limb from limb. Either way, Orpheus finally joined his beloved Eurydice in the Underworld, while the muses put the lyre among the stars with the approval of Zeus, their father.

Vega and other stars of Lyra

Ptolemy knew the constellation’s brightest star simply as Λύρα (Lyra), the same name as the constellation itself. The name we use for this star today, Vega, comes from the Arabic term al-nasr al-wāqi’ meaning the swooping eagle or vulture. The word nasr can mean either eagle or vulture, while wāqi’, from which the name Vega derives, refers to the bird’s falling or swooping motion. This description came about because the Arabs visualized Vega and the two nearby stars Epsilon and Zeta Lyrae as an eagle or vulture with folded wings, diving down on its prey. It was one of a pair of eagles visualized by the Arabs in this part of the sky; the other, in Aquila, was formed by Altair and its two flanking stars which gave the impression of an eagle soaring with wings outstretched – see, for example, this 13th-century Persian astrolabe. On European star maps the constellation was often depicted as an eagle positioned behind a lyre, merging the Arabic and Greek traditions, as on the illustration from Bode’s atlas above.

Beta Lyrae is called Sheliak, a name that comes from the Arabic word for ‘harp’, al-silyāq (or shilyāq), in reference to the constellation as a whole. Gamma Lyrae is called Sulafat, from the Arabic al-sulaḥfāt meaning ‘the tortoise’, after the animal from whose shell Hermes crafted the lyre.

Stringing the lyre

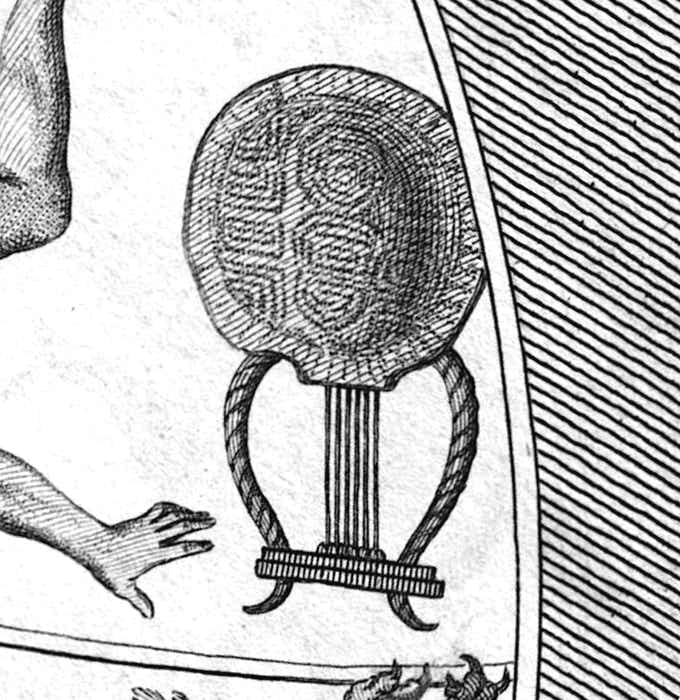

Although Greek mythology specified that the lyre had seven strings, one for each of the Pleiades, most chart makers did not show it that way. Bode in his Uranographia (main image above) drew the lyre with eleven strings, Bayer showed nine, and Jamieson eight, while Hevelius topped them all with 13 strings. The ancient Farnese globe acknowledged mythology by showing Lyra as a tortoiseshell but with only six strings and space for a seventh, evidently representing the ‘lost’ Pleiad. The classically correct Flamsteed also fitted the lyre with six strings but left room for another three, perhaps as an indication that nine Pleiades are visible to the naked eye under good conditions.

Chinese associations

Vega and the adjacent stars Epsilon and Zeta Lyrae were known in ancient China as Zhinü, the weaving girl. In a popular Chinese folk tale the weaving girl was said to be a granddaughter of the celestial emperor. She made beautiful silks for the gods and goddesses, but she fell in love with a lowly cowherd, represented by the star Altair in Aquila. After they married and started a family, both began to neglect their duties. To prevent further interruption to their work the celestial emperor harshly separated them, placing them on opposite sides of the Milky Way. Cowherd was left to bring up their two sons, represented by the stars either side of Altair. Thereafter, the couple were allowed to meet on only one night each summer, when magpies bridged the Milky Way with their wings. This annual meeting of the lovers is celebrated by the Qixi festival, held on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, usually a date in August (or sometimes the end of July).

The four stars Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Iota Lyrae formed Jiantai, a place like a bureau of standards for calibrating water clocks (clepsydras) and sundials and for tuning musical instruments. An older interpretation of this constellation says that it originally represented the loom used by the weaving girl Zhinü (Vega).

A line of five stars from R Lyrae via Eta and Theta Lyrae and on into Cygnus formed Niandao, a route followed by the Emperor when travelling between palaces.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Lyra was shown as a tortoiseshell with six strings on the Farnese globe. This engraving was made by Louis-Philippe Boitard and published in 1747.