Exploring the Moon

A history of lunar discovery from the first

space probes to recent times

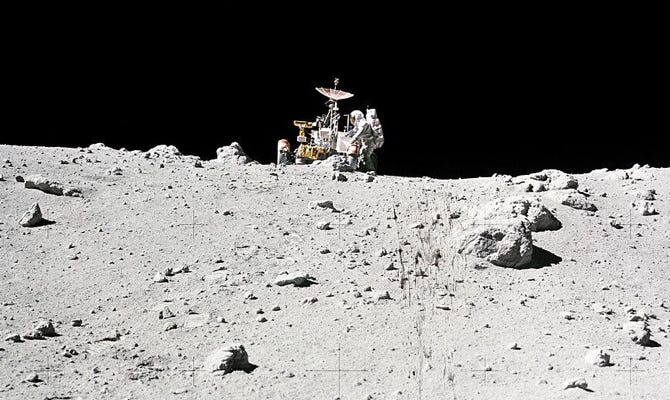

Heading for the hills

The search for fragments of the Moon’s ancient crust was continued by Apollo 16, which landed in a rugged highland area near the crater Descartes. Geologists expected this area to consist of lava flows more ancient than those of the lowland plains, but they were wrong.

Astronauts John Young and Charles Duke soon realized that the rocks around them were broken and shattered ejecta from ancient impacts that excavated some of the Moon’s great lowland basins, possibly both Mare Imbrium and Mare Nectaris. The Descartes highlands were therefore similar in nature and age to the Fra Mauro area sampled by Apollo 14.

However, Apollo 16 did collect one particularly ancient rock (sample 60025, shown in situ at the centre of this photograph) dating back nearly 4.5 billion years, older even than the so-called Genesis Rock found by Apollo 15.

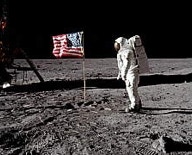

Apollo 17, the final mission of the series, landed on the eastern side of Mare Serenitatis, between the Taurus Mountains and the crater Littrow. Here, dark lava met bright highlands and offered many different types of rock samples, including plenty of large boulders. Astronauts Gene Cernan and geologist Harrison (‘Jack’) Schmitt set new records by spending three days on the Moon, driving 35 km and collecting 110 kg of rocks.

Study of these rocks back on Earth established that the impact that formed the Mare Serenitatis basin occurred 3.9 billion years ago, while the lavas that filled the basin flooded out between 3.7 and 3.8 billion years ago. Lunar observers can see that the Apollo 17 landing site is crossed by a bright ray from the prominent impact crater Tycho, 2,000 km away. Arrival of this ejecta apparently caused landslides on the surrounding mountains about 100 million years ago, when Tycho was formed.

A highlight of the Apollo 17 explorations was the discovery of orange soil, consisting of microscopic glass beads, near a crater 110 metres wide and 20 metres deep called Shorty. At first it was thought that the soil was young, like the crater, but it turned out to be 3.6 billion years old. Geologists think that the tiny beads were caused by a volcanic eruption akin to fire fountains on Earth. Soon after formation, they were buried beneath a subsequent lava flow until being exposed by the impact that caused Shorty, perhaps 30 million years ago.

When Apollo 17 splashed down on 1972 December 19 it brought the first era of manned lunar exploration to a close. No humans have been to the Moon since.

Among the rocks at the Descartes highlands

Heading for the hills

Apollo 17 geologist-astronaut Jack Schmitt collects samples with a rake