A BRIEF HISTORY OF HALLEY’S COMET

Revised extracts from A Comet Called Halley by Ian Ridpath

(Cambridge University Press, 1985)

Awaiting the Comet

Awaiting the Comet

Public anticipation of the reappearance of Halley’s Comet in 1910 was immense. Tunesmiths composed songs to serenade the heavenly visitor, and poets burst into verse. Products such as Bird’s Custard and Pears’ Soap featured the comet in their advertising: ‘Pears’ soap is visible day and night all over the world’ was one slogan. Even before the comet was visible to the naked eye, people wrote to the Royal Observatory to report their sightings, which turned out to be misidentifications of the bright planets Venus and Jupiter and in one case the Andromeda Galaxy.

For a while, though, it looked as if Halley’s Comet would be upstaged by a pretender: a second comet, which appeared unexpectedly in the dawn sky in 1910 January, and was first seen by miners in Johannesburg leaving night shift. For a few days it became visible in daylight and as a result it is known as the Daylight Comet of 1910. But it had faded from view by the time Halley’s Comet bowed into the morning sky in mid-April.

To an observer in Accra, west Africa, Halley’s Comet appeared ‘like a flaming sword with jewelled hilt’. Over the next few weeks its tail stretched upwards like a searchlight beam illuminating the vault of the heavens. In early May, Halley’s Comet lay near the brilliant planet Venus, and superstitious Englishmen marked that this coincided with the death of King Edward VII.

When the public heard that the Earth was due to pass through the comet’s tail, there was widespread disquiet. A family contemplating a sea journey inquired of the Royal Observatory whether the comet would cause storms and gales ‘or other violent atmospheric disturbances’. They were assured it would not.

A correspondent with a taste for apocalyptic prose confided to the Observatory his suspicion that the comet’s tail, in contact with the atmosphere, would ‘cause the Pacific to change basins with the Atlantic, and the primeval forests of North and South America to be swept by the briny avalanche over the sandy plains of the great Sahara, tumbling over and over with houses, ships, sharks, whales and all sorts of living things in one heterogeneous mass of chaotic confusion’. The Observatory tersely marked the letter ‘No reply’.

Other reactions ranged from the light-hearted to the grotesque. From Paris it was reported that restaurateurs were preparing comet suppers for the great occasion, and comet postcards and souvenirs were selling well. In the USA, churches were packed with people who feared that the encounter with the comet signalled the end of the world. A shepherd in Washington State was reported to have gone insane with worry about the comet, while in California a prospector nailed his feet and one hand to a cross and, despite his agony, pleaded with rescuers to let him remain there.

Gas attack!

Cyanogen gas, a poison, had been detected spectroscopically in the tail of Comet Morehouse in 1908, so people feared, understandably, that they might be poisoned by gases from the tail of Halley’s Comet. From Chicago it was reported that women were stopping up doors and windows to keep out the toxic vapour. In Haiti a voodoo doctor sold comet pills to ward off the evil influence of the comet, as did two swindlers in Texas who also did a good trade in leather gas masks. Purchasers were told that the pills (actually made of a harmless combination of sugar and quinine) would help them withstand the gases of the comet’s tail. Police arrested the men but were forced to let them go again when the gullible victims campaigned for their release.

Astronomers tried to reassure the public that there was no danger. For one thing, the head of the comet would come no closer to us than 24 million kilometres. Some scientists thought that a meteor shower or an aurora was possible, but most held to the opinion that there would be no observable effects at all. In fact, the Earth had passed through a comet’s tail at least once before, that of Comet Tebbutt in 1861 June, and nobody noticed a thing. ☄

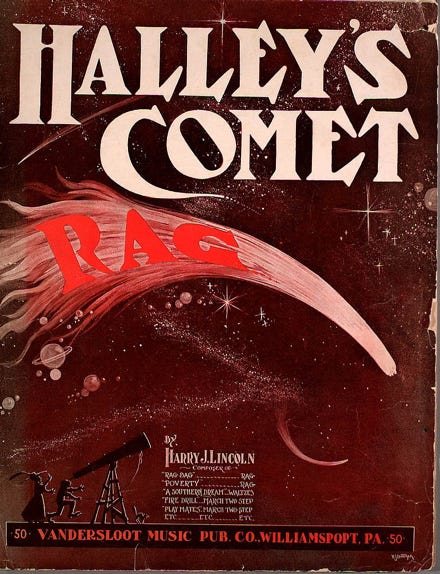

Halley’s Comet Rag was among the tunes composed to serenade the Comet at its visit in 1910.

(Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.)

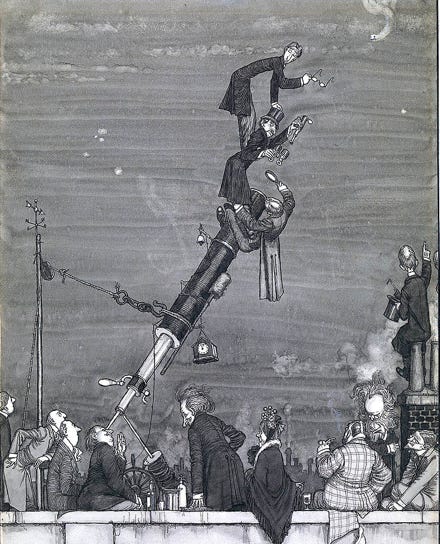

Cartoonist Heath Robinson’s view of astronomers awaiting Halley’s Comet at Greenwich Observatory.

(National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.)